his plan possesses several clear characteristics. As Peter Drucker observed, it’s the obvious that needs to be pointed out:

- It’s positive

- It tracks real food, not nutrients.

- It tracks weight, not calories.

- The food cateogries are designed to help meal planning.

- It requires you to drink a lot of water.

- It leaves room for you to eat freely

Let me elaborate.

It's Positive.

The Positive Eating Plan is positive in two ways:

- It focuses on increasing healthy food consumption, rather than restricting unhealthy ones.

- It uses science to remove unnecessary worries, not to introduce new ones.

You can not make people do the right thing by telling them not to do the wrong thing. This plan does not have a negative list or “not-to-exceed” limits. It only requires you to eat enough of the right foods. I know I am repeating myself. But some people don’t believe a diet is real unless they suffer.

It’s a well-established fact that highly restrictive diets are unpopular and unsustainable. A recent study published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition confirmed that even when meals are prepared and delivered to participants, adherence to strict diet plans remains low.

It Tracks Real Food, not Nutrients.

Food is far more complex than the simple sum of its chemical components. While it is widely accepted that carbohydrates and protein each provide 4.5 kcal/g and fat offers 9 kcal/g, this calculation assumes no interactions occur between different foods during digestion. However, we know this is not the case. For instance, dietary fiber can increase the excretion of nitrogen and fat, meaning that a high-fiber diet results in less absorption of protein and fat. Similarly, the glycemic index of ice cream is lower than that of apples, as the fat in ice cream alters the rate at which sugar enters the bloodstream. Furthermore, a recent study has shown that consuming a small amount of vinegar before a carbohydrate-rich meal can slow the rise in blood glucose levels.

The history of dietary advice underscores the complexity and evolving nature of nutritional science. In 1863, the pamphlet Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public argued that cutting out starch was key to weight loss. By the 1950s, Ancel Keys’ Seven Countries Study had linked saturated fat to heart disease. High-protein ketogenic diets have gained popularity, partly based on the notion that Arctic populations have thrived on meat-heavy diets for millennia. Yet, it turns out that the Inuit, often cited as a model, cannot enter ketosis due to a gene mutation that prevents ketone production. We seem to have run out of edible macronutrients.

The situation with micronutrients isn’t any better. In the book “Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us”, Michael Voss wrote that scientist at General Foods working on a synthetic orange juice had a big problem: when they added in all the vitamins and minerals to replicate the nutritional profile of real orange juice, it tasted bitter and metallic. The marketing people told the scientists that people primarily associated orange juice with Vitamin C, not all the other nutrients. Luckily, vitamin C was the one nutrient that didn’t have an awful taste. Vitamin C was an acid, so it also has the benefi of balancing out the added sugar. Thus born Tang, one of the blockbuster products in the food industry.

There is an extra twist in the Tang story. NASA didn’t pick Tang because it was nutritious but because it didn’t add much bulk to digestion. NASA was concerned about toilet constraints in space.

The association between vitamin C and good health has its own intriguing backstory. In 1970 Linus Pauling, the only person who was awarded two unshared Nobel Prizes (in Chemistry and Peace), published “Vitamin C and the Common Cold,” urging the public to take 3,000 milligrams of Vitamin C every day - approximately 50 times the recommended daily allowance. Pauling spent the remainder of his career promoting the supposed health benefits of vitamin C and fiercely attacking those who challenged his claims. Yet, at least 15 studies have now shown that vitamin C doesn’t treat the common cold. The data also indicate that high doses of vitamins and supplements can actually increase the risk of heart disease and cancer. The fascinating history was expertly recounted in the book Do you believe in Magic? The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative Medicine.

There is still much that scientists do not fully understand about nutrients. he nutritional fiasco known as margarine comes to mind. The scientific literature on the subject is not only vast but also filled with contradictions. As Artemus Ward wryly observed, “The researches of so many eminent scientific men have thrown so much darkness upon the subject that if they continue their researches, we shall soon know nothing.”

Whole foods are inherently complex, and when we reduce them to isolated nutrients, we disregard an unknown wealth of information that could be crucial to understanding their true impact on our health.

It Tracks Weight, not Calories.

There are fundamental issues with tracking calories: It’s both futile and extremly difficult.

Low calorie intake does not guarantee a calorie deficit. The human body strives to maintain homeostasis, a fancy word that means the body tries to match energy expenditure to energy intake. In his book Burn: New Research Blows the Lid Off How We Really Burn Calories, Lose Weight, and Stay Healthy, Herman Pontzerr, an associate professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University, illustrates this point vividly: “The average American adult gains about half a pound per year, an error or around 1,750 kcal. That’s only about 5 kcal per day, or less than 0.2 percent of daily energy expenditure. In other words, without thinking much about it, we match our daily energy intake to within 0.9 percent of our daily expenditure.”

Moreover, this does not even account for individual variations. Large bodies tend to burn more calories overall. Small bodies burn more calories per unit weight. According to Pontzer’s research, even after accounting for body sizes, many in the population fall above or below the trend line — their expected daily expenditure — by 300 kcal per day or more. In other words, nobody is average.

Anyone who has attempted to determine the calorie content of food knows it often requires navigating a maze of choices. Take, for example, the simple food French Fries. If you search for “French Fries” in the USDA FoodData Central, you will be met with over 1,000 results. There are entries for fries from Applebee, Denny’s, Mcdonald’s, homemade from fresh potatoes, homemade from frozen potatoes, target store fries, vending machine fries, and even those from Giant Eagle Inc. They are not all equal. The McDonald’s French Fries have 15% more calories than the Burger King French Fries, which in turn have 40% more calories than “Potato, Fresh fries, from fresh, fried.” That’s a difference of about 100 kcal for a small serving.

What accounts for this variation? One clue lies in the water content. According to the data, 36.6% of McDonald’s fries is water by weight, compared to 44% for Burger King’s fries and 65.1% for homemade fresh fries. When food is fried in oil, steam bubbles out. That is water leaving the food in the form of steam. As water dries out, oil moves in. How much water is replaced by fat depends on how long the food is immersed in the frying oil and how old the frying oil is.

Oil and water don’t mix. As steam rushes out of the food, it pushes the oil away, meaning that hot oil has limited contact with the food’s surface. This is why achieving the same golden crust at home can be challenging—your oil is likely too fresh, and the food doesn’t reach a high enough temperature for the Maillard reactions that create browning. As oil is repeatedly heated, its fat molecules break down and rearrange, forming surfactants, or emulsifiers. These chemicals have one end that is hydrophilic (attracted to water) and another that is hydrophobic (attracted to oil). “Broken-in” oil, which contains more surfactants, conducts heat more efficiently into the food by better mixing steam with hot oil and increasing their contact with the food.

McDonald’s likely has a precise process to ensure all fries are cooked for the same duration, but each batch of oil is used to fry many batches of fries. The concentration of surfactants in the oil changes over time, which can affect the calorie content of the fries.

When using food tracking apps, the challenge of accurately recording calorie intake becomes apparent. In two apps I recently tested, one offered 12 options for fries and the other 18. To make the app usable, developers have had to significantly narrow down the options. The sheer complexity of calorie data—often sourced from vast databases like FoodData Central—makes these apps cumbersome and potentially inaccurate. Food Database is where calorie tracking apps go to die.

Consider that fries are made from just three ingredients: potatoes, salt, and oil. Yet even determining their calorie content is difficult. Now imagine trying to calculate the calories in a dish like Champignon De Bois from The French Laundry Cookbook, which claims, “We love the simple fun of this dish.” This “simple” appetizer, however, contains three dozen ingredients. While it may be simple and enjoyable to eat, the task of looking up and recording the calorie content is anything but simple—or fun.

Champignon de Bois (from the French Laundry Cookbook)

What about the label on food packages and restaurant menus? They are regulated by FDA, and FDA allows up to 20% variation. That is pretty strict, considering all the possible deviations in preparing an item as simple as fries.

Compared to calories and nutrients, weight is the most straightforward metric to track,offering all the benefits of food tracking without the complexity. Your weight is the output of your life choices; the food you eat is one of the most important inputs. Tracking the input—what you eat—offers several advantages compared to obsessing over the output, your body weight:

- The inputs are within your control; the output, such as body weight, is not directly manageable - as anyone who has ever tried losing weight is painfully aware. In “Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon,” two former Amazon executives wrote about how Jeff Bezos focuses on the “controlled input metrics” instead of the Amazon stock price. You make sure the inputs are right, and the output will take care of itself. It’s too late to change the input once the output has materialized.

- It liberates you from the depressing thought of “portion control.” This positive plan does not prescribe any upper limit. The total weight of the food serves as a constant reminder to monitor your intake. This method provides a simple, objective, and indisputable metric. As long as your diet remains balanced, the total weight of your food is the most meaningful measure.

- You can get a rough idea of how full your stomach is. Most adults’ stomachs can hold about 1 liter of food. Since a large portion of most food is water, it’s reasonable to assume 1 kilogram of food will start stretching your stomach. You can not shrink your stomach without surgery, but if you are mindful of its capacity, you might just be able to train your stomach to send the “I am full” signal for less food.

- For someone serious about weight control, it’s relatively easy to refrain from overeating at the dining table. It’s much harder to be mindful of everything you put in your mouth. But those small things add up. The three times you grab “just one” cookie when you pass the cookie jar? That’s 150 grams.

- Forcing yourself to weigh everything you eat itnroduces a slight “speed bump.” It’s the ultimate slow food move.

Let’s take a step back and consider our original goal of weight control. How much does one calorie weigh? What do you lose when you lose weight?

In our bodies, carbohydrates and fats react with oxygen to produce energy—proteins generally play a minimal role in daily energy requirements. The primary byproducts of these reactions are carbon dioxide and water. As you inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, each breath results in the loss of carbon atoms, which translates into weight loss. Therefore, unless you are increasing your respiratory rate, you are unlikely to lose weight at a faster pace. This explains why losing more than about 0.5 pounds per day is improbable. Any rapid weight loss is likely attributable to water loss, except in cases of diarrhea.

Food weight, however, is often misleading due to its high water content. For example, dark chicken meat is composed of 77% water, and spinach consists of 93% water. This water is readily processed by the body, meaning that tracking the weight of food alone might overstate the actual mass being consumed. Is that so bad if you are tyring to eat less?

By adopting the metric system for tracking food weight, two potential stressors are eliminated:

- How tightly should I pack my spinach? Tracking food is challenging enough without the added ambiguity of volumetric measurements. Whether piled high or packed down, 100 grams of blueberries always equates to 100 grams.

- Quick: how many tablespoons are in 1/3 cup? Answer: 5.3328. Math is so much easier in the metric system. The United States is one of the only two countries that have not adopted the metric system. The other is Liberia.

Even if you prefer to monitor calories or nutrients, weighing food remains a prerequisite before identifying, categorizing, and calculating its nutritional value - a process in which the math is the easy part. Now that’s something you don’t hear every day!

If you want to control weight, control weight.

The Food Categories Are Designed to Help Meal Planning.

They are not there to win any academic prize. They are designed to help when you are standing in front of an open fridge, or in the grasp of a pang of hunger, simply wanting to eat something - anything.

When planning a meal, the instinctive approach is to combine protein, vegetables, and carbohydrates—the core components of this plan. Beans, including tofu and plant-based meats, serve as excellent sources of plant proteins, making this plan accessible to vegans as well.

Preparing for challenging moments is crucial to the successful implementation of any difficult plan. A new category of recommended snacks—nuts, cheese, yogurt, and fruits—provides healthy options that are both satisfying and convenient. These snacks are packed with beneficial nutrients, including unsaturated fats, protein, antioxidants, and vitamins, ensuring you are filled with “good stuff.”

Don’t put yourself in a position where your only salvation is Snickers.

It Requires you to Drink a lot of Water.

The benefits of staying sufficiently hydrated are well documented. I will highlight just one. The initial step in fat digestion is hydrolysis, a process whose name is derived from the Greek words hydro (water) and lysis (dissolution), meaning chemical breakdown by water. Digestion of fat requires water.

It Leaves Room for You to Eat Freely.

This plan does not have enough food to feed a healthy adult, who typically needs between 2500 to 3000 kcal a day. If you consume only the minimum amount from each category, your intake will total approximately 1,600 calories. This deliberate shortfall ensures that the promise of “whatever else you want” is not an empty one. Go ahead and add that béarnaise sauce to your poached salmon.

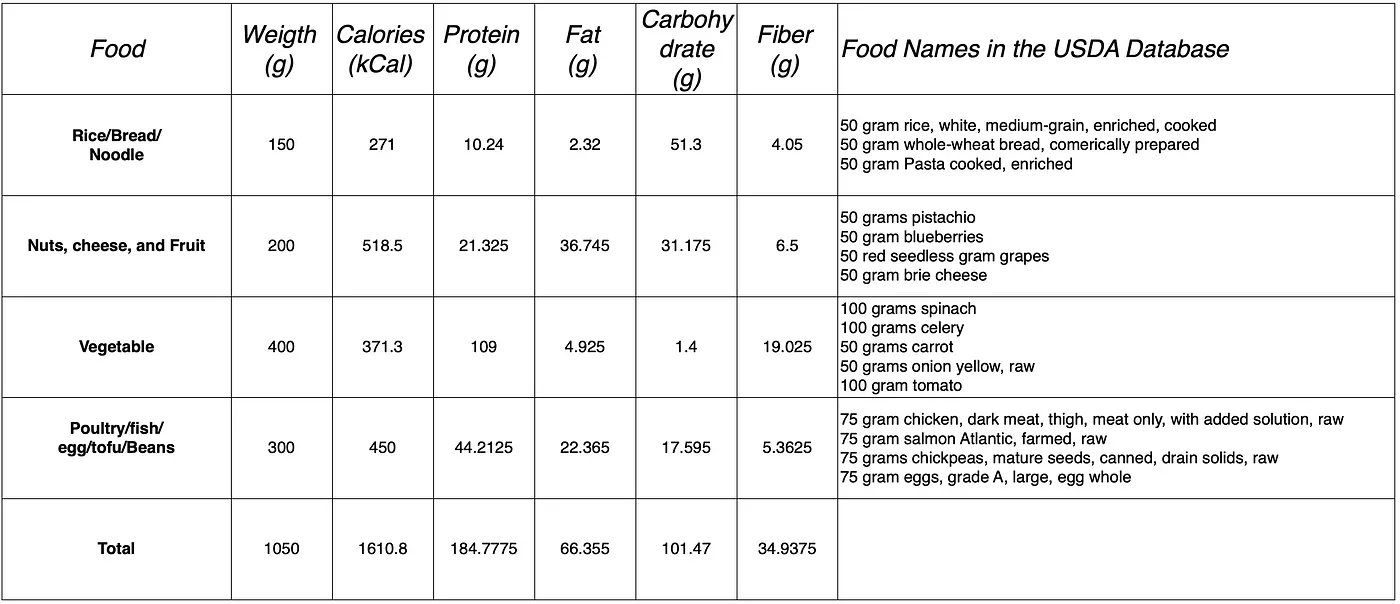

Here is the detailed nutritional information for the plan, if you must know.