More Critical Cooking Temperatures

Water boils at 100⁰C. It’s a useful and convenient visual cue for the cook to tell the temperature without a thermometer. However, a lot of the time, you are not cooking with just water. When you are cooking a very thick liquid like tomato sauce, normal convection is impeded. Different parts of the liquid can have significantly different temperatures. The top may be lukewarm while the bottom is scorched. That’s why you need to keep stirring.

If you add alcohol to water, the resulting mixture has a new boiling point between the boiling points of water and pure alcohol. It’s incorrect to say the alcohol boils off first. The vapor of this mixture contains both alcohol molecules and water molecules. At a temperature lower than the water’s boiling point, this vapor does have a higher percentage of alcohol—that’s how distillation works.

An obvious but often forgotten fact is: anything cooked in water is cooked at a temperature under the water boiling point, 100⁰C. You can call it browning, searing, or stir-frying. But as long as there is water around, you are just boiling or steaming. This brings us to another important phenomenon for cooks: the wet bulb temperature.

If you put two thermometers in an oven, one by itself and the other wrapped in a wet cloth, they will give different temperature readings. The dry thermometer will read the air temperature inside the oven, while the “wet bulb” thermometer will read a lower temperature. That’s because it takes heat to evaporate water. We feel warmer in a humid climate than in a dry climate because, under higher relative humidity, less water evaporates from our skin, and we don’t get as much benefit from the cooling effect of evaporation. When food is not dried out, it is not cooked under the temperature of the medium, whether it’s hot air or hot oil (yes, fried food experiences wet bulb temperature too), but under the wet bulb temperature.

Many flavor-producing chemical reactions happen above 100⁰C. They will not take place until all the water has evaporated. The first of these reactions, and considered by many the most important, is the Maillard reactions. They are a series of reactions between amino acids and simple sugars. Maillard reactions do happen at lower temperatures. Traditionally, the Chinese century eggs (皮蛋) are made by coating the egg in an alkaline mixture of wood ash, calcium oxide, and salt. The egg white and yolk undergo Maillard browning to arrive at their unique colors.

But you don’t want to wait a century. Maillard reactions accelerate around 120⁰C to 130⁰C. The results are hundreds of new compounds, with strong and pleasing flavors and aromas. Maillard reactions happen in almost all kinds of meats, resulting in slightly different aromas from their specific combination of amino acids and sugars. Due to their chemical structure, most products of Maillard reactions appear brown.

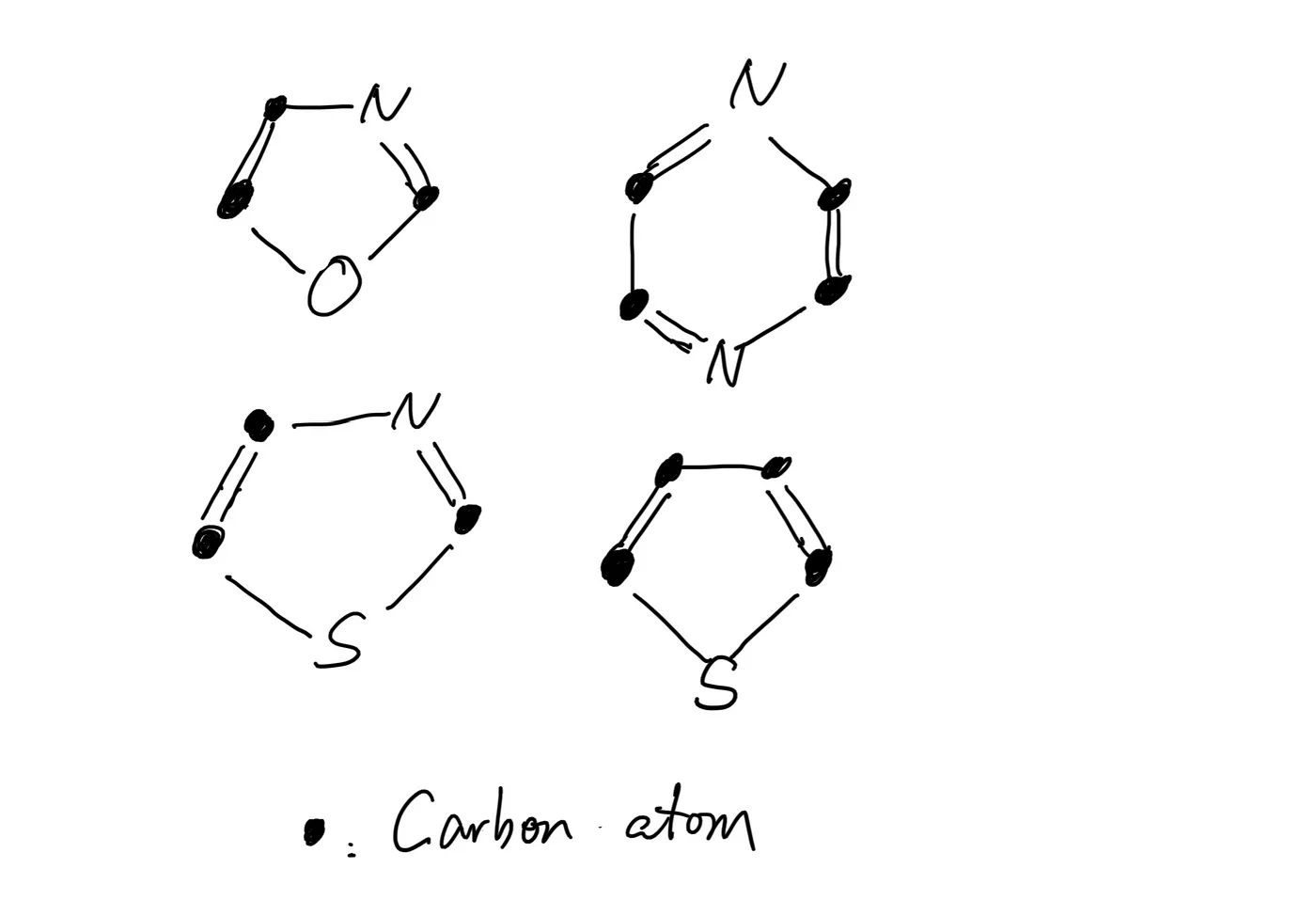

The Maillard reaction is sometimes called the browning reaction because the products of Maillard reactions have rings or a collection of rings in their molecular structure, which reflect light in such a way that makes them appear brown.

Some products of the Maillard reactions

Exactly what happens during Maillard reactions is not completely understood yet. But as a cook, these are what you should know about Maillard reactions:

- Maillard reactions do happen at lower temperatures, but they accelerate around 130⁰C. This means they cannot happen fast enough in the presence of water.

- It’s a reaction between protein and simple sugar. You need both for it to happen. That’s why meat browns better with butter, which has both protein and sugar (lactose). Most meats do brown without added sugar, though, because they contain the sugar glycogen. This is most notable in scallops.

- It happens faster in an alkaline environment. That’s why some bagel makers dip their dough in a lye solution before cooking them. It's also the reason for baking soda in the recipe for the caramelized carrot soup in Modernist Cuisine.

The Maillard reactions are not the only reactions that produce brown pigments, though. At 170⁰C, sugars begin to break down, resulting in a sweet, nutty flavor and brown color. This is called caramelization, which is often confused with the Maillard reaction.

It’s tempting for a cook to always strive to induce the Maillard reactions and caramelization. However, I would urge you to think of ways to accentuate and present the unique flavor of the ingredients, instead of always falling back on the familiar and the commonplace.

Next, at 186⁰C, sucrose melts. Some people take advantage of this fact to calibrate the temperature of their ovens. I have never seen an oven that can get to a temperature and stay there. Their temperatures fluctuate around the set point, and the temperature differences among different spots in the oven are significant even after a long preheating period (immersion circulators do a much better job controlling the temperature of water baths). All times and temperatures in recipes that involve ovens are just suggestions. To control what comes out of the oven, I would only trust multiple thermometers and carefully designed experiments.

Around 190⁰C, olive oil starts to smoke. We don’t care so much about the boiling point of cooking oils because their fat molecules decompose into other molecules at temperatures way below their boiling point. Smoke is the gaseous product of decomposition. We discussed earlier that when atoms come together, their electrons pair up and the electron clouds merge. They prefer that arrangement because it puts them in a lower energy, more stable state. Some of the products of smoking are molecules with unpaired electrons. They feverishly look for other chemicals to react with so their single electrons can be in a stable relationship. These species are called free radicals. Free radicals are the opposite of antioxidants. Needless to say, they are not good for your health.

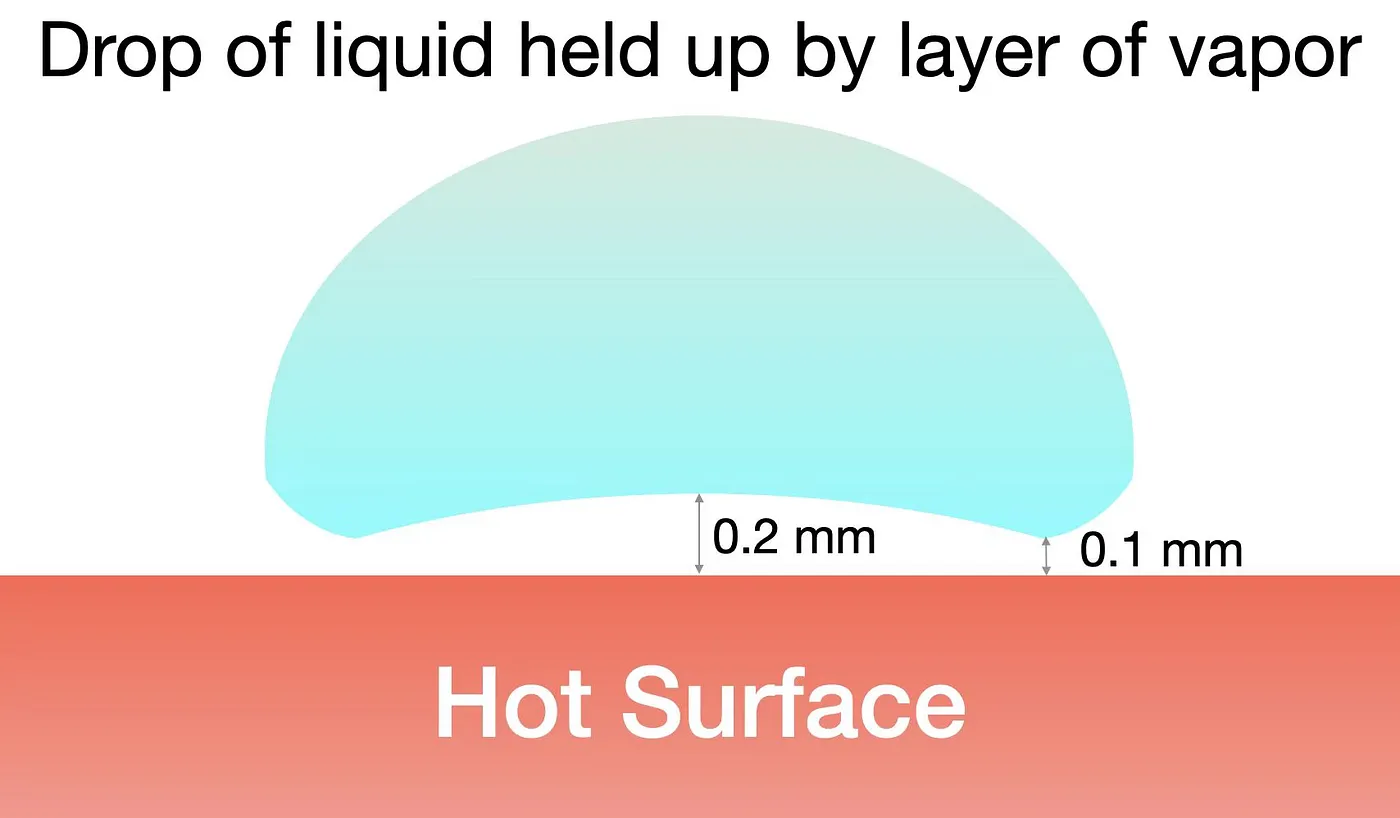

If you heat the pan to 200⁰C, and splash a few drops of water on it, they will slide along the hot surface like little balls instead of being vaporized. This is the Leidenfrost effect. The temperature of the hot surface is so much higher than the boiling point of water that an insulating layer of vapor is formed upon initial contact. The remaining water in the droplet just rests on this air cushion like a hovercraft.

The Leidenfrost effect

To avoid having the food stick to the pan, you should wait until the pan is really hot before dropping the food. The sizzling sound you hear is the water on the surface of the food vaporizing, creating the steam cushion.

The highest temperature for most home ovens is around 260⁰C/500⁰F. But commercial pizza ovens routinely reach 500⁰C. You want to bake your pizza crust at a temperature of at least 315⁰C/600⁰F to get the most crispy yet fluffy crust. High heat for a limited amount of time is the secret ingredient of great pizzas.

Speaking of high heat, the temperature of a charcoal grill can be as high as 650⁰C/1200⁰F. In comparison, a propane grill can only get up to about half the peak temperature. According to the Stefan-Boltzmann law (yes, that Boltzmann), the radiated energy is proportional to the 4th power of the surface temperature. That’s why charcoal grills can produce a better crust.

There is a lot more to be said about cooking and temperature. But hopefully, this discussion has convinced you of the importance of precise and consistent temperature control. No amount of scientific knowledge can replace the experience and intuition about the state of food that professional cooks acquire from practice. Better tools need to be developed for home cooks to make up for some of that deficiency. In the meantime, frequent tasting during cooking helps, but be careful not to burn yourself.