You Can't be Picky with What You Eat If You Want to Survive

When our ancestors went out to look for food, they didn’t have ATVs. In the Pleistocene, they didn’t even ride horses. They had to expend their own energy. One cup of spinach contains only 7 calories. I doubt it’s enough to replenish the energy we spend to chew and digest it, not to mention walk a mile to collect it. The return on investment was just too low. Common sense tells us a smart caveman would have passed a spinach field without a second thought. A dumb caveman would not have been our ancestor.

But common sense also tells us that hunting big game had a low chance of success, especially in the Paleolithic, when, by definition, our forebears were armed with rudimentary tools. The odds of a successful hunt were as meager as 3% on any given day, based on data gathered from modern hunter-gatherer societies in Africa.

Contemporary hunter-gatherer societies exhibit a notable breadth in their dietary patterns. The Gwi San people in Botswana obtain 80% of their calories from carbohydrate-rich sugary melons and starchy roots. The Yanomami people in the Amazon rainforest are foraging horticulturalists (they cultivate plants on a small scale), while the Sámi of Scandinavia are pastoralists (they raise livestock on natural pastures). The Hadza people in Tanzania are probably the most studied hunter-gatherers. They have a diversified diet: tubers, berries, meat, baobab, and honey.

However, we should be careful drawing conclusions about our ancestors’ diet from modern hunter-gatherer communities. They may not live like us, but they haven’t stopped evolving and reacting to the changing environment over the last 10,000 years. For the same reason, an American would not use present-day British English as a reference point for pre-Mayflower speech in the UK. Some of these changes are even man-made, as opposed to natural. If Martians landed in North America today, they might conclude that Native Americans evolved to live in remote and extremely harsh environments. The Lacandon people living in the jungles of Mexico are one of the most isolated indigenous groups. They used to be held up as an example of what primitive life would have been like if people didn’t start farming. But we now know they are descendants of Mayan people who ran away from the Spanish colonists.

Some of the best scientific evidence of what humans evolved to eat can be found in our anatomy. You can tell from the shape of teeth what food they are designed to eat. Carnivores have teeth that are sharp and pointed. They have elongated and pointed canine teeth to capture and hold onto prey. They use their teeth like guillotines to cut and tear flesh and bones. Even their molars have short cutting edges. On the other hand, herbivores have molars that are broad and flat, even with grooves like a washboard, so they can easily grind fibrous plant materials. They have prominent incisor teeth that are optimized for biting off plant parts. Herbivores move their teeth laterally, while carnivores move their teeth up and down, which results in different joints and muscles.

Just because teeth are adapted to eat certain foods does not mean that’s what their owners normally eat. The mangabeys, monkeys living in Kibale National Park of Uganda, are a case in point. They normally have no problem finding fleshy fruits and soft young leaves in their habitat. However, in 1997, there was a particularly strong El Niño event. The mangabeys couldn’t find their preferred foods. However, they were able to shift to bark and hard seeds because they have thickly enameled, strong teeth and big, heavy jaws to crush hard, brittle foods. Their anatomy might not help the mangabeys get the most out of their preferred food, but it helps them survive once-in-a-lifetime extreme weather.

Human teeth do not seem to have adapted to any particular kind of food. We have canines too, but they are not sharp enough to tear raw flesh effortlessly. Our incisor teeth are not sharp enough to cut food up (that’s why the pizza cutter wheel was invented). No normal person will try to crack open walnuts with their teeth like squirrels. (If you try, you may find out something you don’t want to know: how much a dental crown costs.) We may be able to chew grass, but our guts cannot handle it. Compared to most primates, our guts are smaller, but our brains are bigger. We see an interesting parallel in animals: folivores (animals who primarily feed on leaves) tend to have smaller brains and larger guts than closely related frugivores (animals who mainly eat fruits). That makes sense: leaves are everywhere. An animal doesn’t have to work very hard to find them. Sweet fruits are harder to find. An animal has to know when and where to get them and know to avoid the poisonous ones. But once they are found, they pack more energy and are easy to digest. It seems we have evolved to eat nothing in particular, as long as it’s easy to chew and easy to digest. How did that happen? There are some clues in the fossil records from two archaeological sites.

At Olorgesailie, a sedimentary basin on the floor of the East African Rift Valley, an interdisciplinary team of scientists drilled a hole as deep as they could into the earth. They removed a 139-meter-long cylinder of earth, which turned out to represent 1 million years of environmental history. Earlier, we talked about ancient lakes coming and going. The contents of the layers of sediment recovered from deep inside the earth proved the environment in this part of Africa flipped back and forth between warm and wet and cool and dry.

Two important findings from those layers of sediment are:

- After a long period of stability, the environment became more variable around 400,000 years ago. At the same time, anatomically modern humans began to appear.

- The animals found in earlier deposits were grass specialists, but species found in later deposits had more flexible diets. It seems evolution favors less picky eaters.

We could hypothesize that early humans had to eat what was available to them, and what was available to them changed depending on the local biosphere. How did farming change that? The archaeological evidence of how humans lived right before and after the invention of farming was found in the Fertile Crescent.

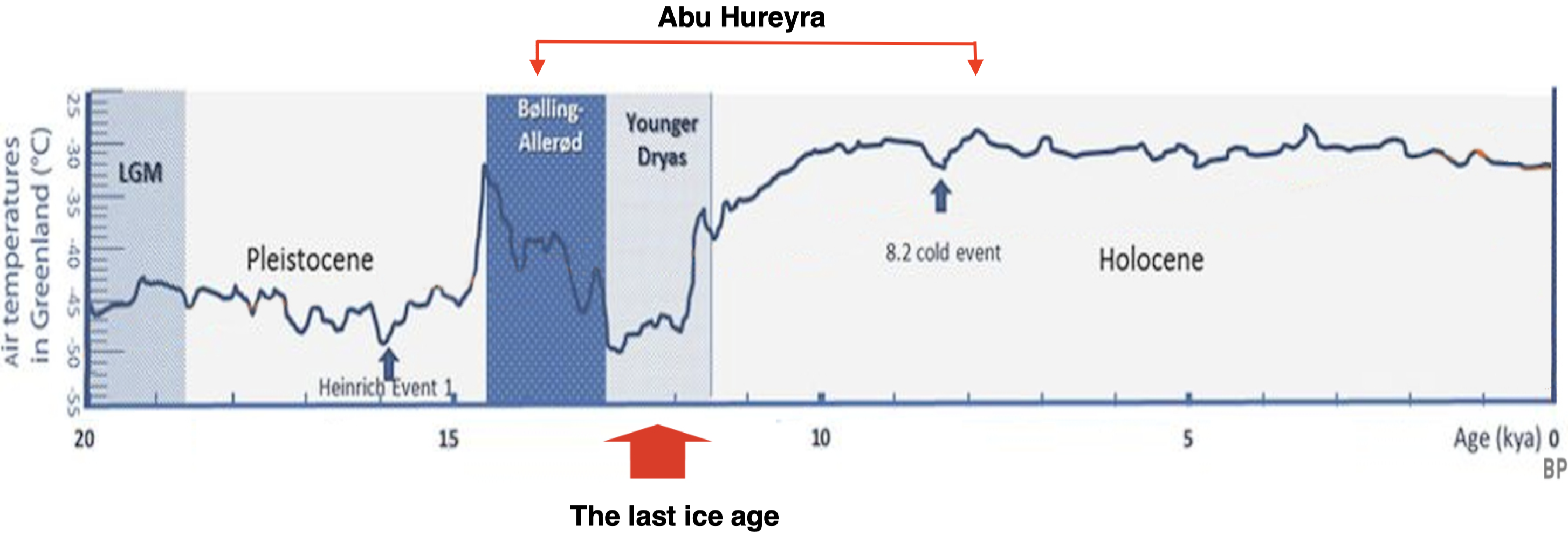

The Fertile Crescent is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Kuwait. It’s believed to be the first region where farming started. Abu Hureyra is an archaeological site in Syria. People started living there about 13,000 years ago until about 7,000 years ago, coinciding with both the transition from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic, and from the Pleistocene to the Holocene. What is particularly relevant for our discussion is that the occupants of Abu Hureyra started as hunter-gatherers but ended up as some of the earliest farmers. In the beginning, the site was a land of abundance. People hunted and gathered along the Euphrates River and in the surrounding woods. Remnants of many wild animals and plants were found in the earlier sediment deposits. The occupants of the village seemed to live on the perfect Paleolithic diet.

Little did they know they were living in the Bølling–Allerød Interstadial, a brief relief between two ice ages. In about 1,000 years, the last ice age, known as the Younger Dryas, would have started. This is the temperature history recorded in the Greenland ice cap:

As the weather became colder and drier, wild foods became harder and harder to find. In the meantime, cultivated rye grains, stone tools for grinding the rye, and lentils and domesticated wheat began to show up in archaeological records. Around 10,000 years BP, when temperatures had risen and the environment became hospitable again, the occupants of Abu Hureyra didn’t go back to their hunting-gathering ways. Instead, evidence showed that domestic cereals and legumes gradually replaced wild plant foods over time, and there was less hunting and more herding.

With agriculture, humans were no longer part of nature, but apart from nature. Our ancestors were evolving to eat what they could find in order to survive the fickle environment, but now they began to evolve to eat what they could produce.

When you can make what you eat, you’re going to make what you want to eat. People had been selectively breeding and cross-pollinating plants and animals for thousands of years before modern genetic engineering existed. Industrial agriculture took it to the next level. Today’s fruits and vegetables are sweeter, have higher yields, look better, and are more disease-resistant. A study showed that cultivated apples are 3.6 times bigger, 43 percent less acidic, and 68% lower in phenolic content than their wild progenitors. It’s an insurmountable problem for anyone who tries to practice the paleo diet: they don’t make ’em like that anymore. Heirloom tomatoes are considered to have pure genes, but the seeds only need to be traced back about 100 years for them to be called heirloom.