Microbiology and Food Safety

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice. Nobody should rely on the correctness of the information presented here. I cannot be responsible for anything that might happen if you follow the advice here.

Food pathogens are biological agents in food that make you sick, either directly or indirectly (through the toxins they release). Common food pathogens include parasites, bacteria, and viruses.

The first line of defense against food pathogens is to buy from reliable sources. Some pathogens cannot be eliminated at home. For instance, if the beef is already contaminated, cooking steak well done will not reduce the risk of mad cow disease. I am not one to vouch for bureaucracy. But like it or not, meat production and distribution are heavily regulated in the United States. For instance, USDA requires an inspector to be present for any slaughterhouse to operate. If you buy from the normal regulated channels, meat should be safe to eat. For example, it’s now extremely rare to find parasites in meat. But as Reagan said, the 9 most terrifying words in the English language are “I am from the government, and I am here to help.” Just google “Creekstone Farms BSE rapid testing.”

The second line of defense is to wash your hands. They touch everything in the kitchen and outside the kitchen. Surgeons wash their hands carefully before they enter the operating room, and so do professional chefs before they start prepping. Here are some tips for washing your hands:

- Wash long enough. It takes time for the soap to do its job. Apple Watch now has a feature that automatically tracks how long you wash your hands. Turn it on.

- A lot of people remember to wash between their fingers but overlook washing their thumbs thoroughly.

- It’s best to use a brush to wash under your fingernails.

This story in Modernist Cuisine shows how hard it is to wash hands well: navy doctors swabbed some UV powder around the rectums of sailors without telling them. The next day, traces of UV powder were found all over the ship under UV light.

Keeping your hands clean is an essential part of the third line of defense: minimizing cross-contamination. It’s a common misconception that raw meat is the only source of food-borne pathogens. Vegetables deserve the same level of scrutiny. What defense does a spinach field have against a sick wild boar defecating in it? That was exactly how the 2006 E. coli outbreak got started. Incidentally, an important benefit of being organized is reduced risks of cross-contamination.

Side towels are a great convenience, but they can also be a medium for cross-contamination. Be mindful of what is on your hands when you wipe them. I keep a small bottle of bleach in my kitchen and regularly disinfect my side towel with diluted bleach.

In reality, unless you treat your food like biohazard waste, it’s very hard to completely eliminate cross-contamination. This brings us to our last line of defense: cooking with heat.

A common food-borne pathogen is bacteria. Most bacteria rely on binary fission (splitting in two) for propagation. Therefore, the number of bacteria grows exponentially. However, it takes time for a bacterial cell to mature enough to split. Researchers in the field of predictive microbiology are working hard to understand how different environmental factors, including temperature, pH value, water activity, and the existence of other organisms, affect the timing of microbial reproduction.

The thermal death time curve of bacteria has been well understood for some time. All else being equal, the life and death of bacteria are regulated by temperature. At really low temperatures (under freezing), bacteria either die or stop reproducing. Above around 5°C, as temperature rises, the bacteria reproduction rate also increases. They grow the fastest at around 40°C. After that, the growth rate decreases. Above 55°C, bacteria start dying. The temperature range between 5°C and 55°C is considered the danger zone for food safety.

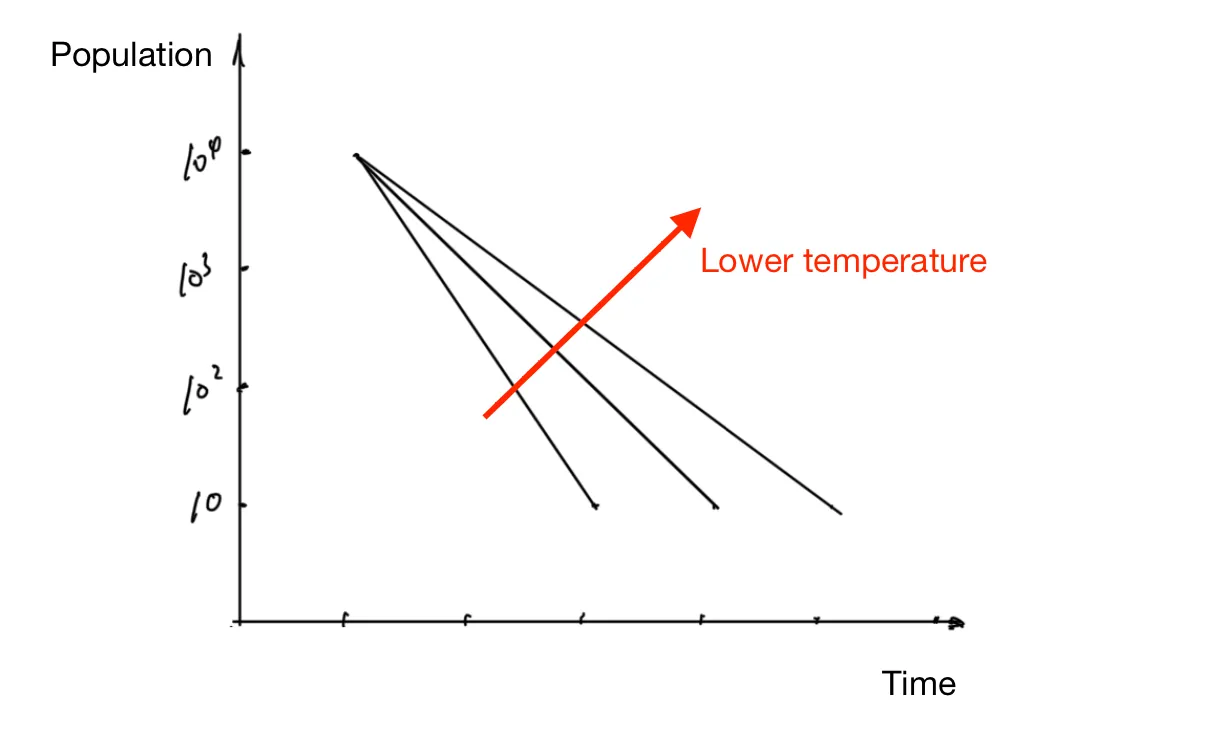

A common misconception is that bacteria are killed, and only killed, under high temperatures. Remember, temperature is the average measure of a random process. When a bacterial cell will die under a certain temperature is also an exercise in probability. When bacteria start dying, if the temperature rises, more bacteria die in a given time; if the temperature is held steady, more bacteria die as time passes.

Thermal death curve

As shown above, there are two ways to achieve the same reduction of bacterial population: higher temperature, shorter time or lower temperature, longer time. In other words, it's "the area under the curve" that counts.

In food sanitation, the reduction in bacteria is often indicated with the D number. 1D means a reduction by a factor of 10. A 2D reduction means only 1/100 is left. According to data published by Vijay Juneja, a research scientist at USDA, these are the temperature and time needed to achieve a 6.5D reduction in Salmonella for chicken breast meat:

- 2 minutes 36 seconds at 63°C

- 20 minutes 56 seconds at 60°C

- 29 minutes 32 seconds at 58°C

- 1 hour 15 minutes at 55°C

Bacteria mostly live on the surface of the meat. The inside of the meat should be clean. However, if you puncture the meat, say, with a meat thermometer, you run the danger of contaminating the inside with bacteria from the surface. If you want to monitor the internal temperature of a piece of steak, you should do it after you have seared the surface of the steak. That’s also why you should crack eggs on a flat surface instead of on the edge of a bowl so that you don’t let shell fragments contaminate the inside of the egg. Burgers made with ground beef should always be cooked to a higher temperature than a piece of intact steak.